One area that has historically seen a lot of interaction between AI researchers and cognitive psychologists is that of a knowledge representation. Researchers have been interested in understanding how we learn, memorize and remember everything we know. And we do know many things – our vocabularies contain up to tens of thousands of words, and, even as we grow older, we learn novel words and have the ability to acquire a new language.

The memory system that stores knowledge about words and, more generally, the knowledge we acquire over a lifetime, is known as the semantic memory. Aside from words, it also stores the information about relationships between the words. Such knowledge can be modelled using semantic networks. Somewhat informally, a semantic network consists of words and connections between them. Connections represent a relationship between two words: for example, two words can be associated with each other, they can be synonymous etc. More formally, semantic network is a graph defined by its set of vertices (words) and edges (links between words).

Cognitive psychologists in late 60s and 70s used such models to explain how the human semantic memory is organized and searched [0, 1]. For example, such models allowed them to predict how long it takes for a person to recognize that a sentence is false. Recent brain imaging studies reveal that a similar organizing principle might be used by the brain, as words similar in meaning activate adjacent brain areas [2].

Another way of representing words is using word-vectors. Such vectors capture statistical regularities in large corpora of text in such a way that similar words will be assigned similar vectors. If we imagine vectors as points in space, those points will be close to each other for similar words. Different methods exist that accomplish the task of assigning words to vectors, and, once again, this topic has been of interest to researchers modelling human knowledge, as well as to those developing algorithms that reproduce human-like language abilities.

In one of my recent projects, I investigated how semantic networks constructed from word vectors compare to semantic networks derived from human word associations. Arguably, the latter can be regarded as psychologically realistic, since they are more likely to reflect the way humans think about words. In contrast, the former (I will refer to them as synthetic networks) are likely to reflect co-occurrence patterns observed in written materials.

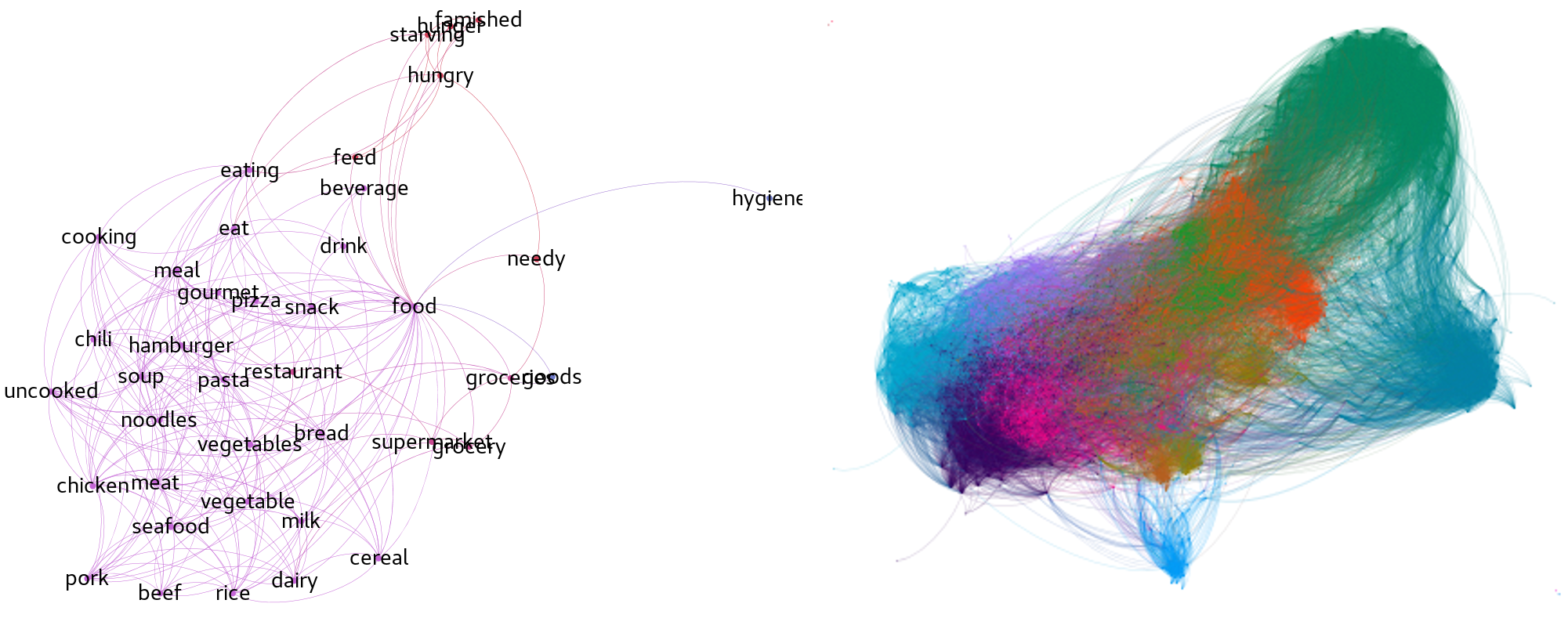

I created different versions of networks and compared them against different criteria. Human networks are known to display small-world characteristics – although they contain many words and only a small fraction of all possible links between the words, any two words in the network can reached within just a few steps by following those links. This is very convenient as it means we can be fairly efficient when searching for words in a vocabulary. In addition, human semantic networks contain clusters of semantically related words (see image above). All synthetic networks networks that I analyzed also show that property.

However, the next two analyses demonstrated properties where synthetic networks either differ from human semantic networks, or they give us results where it’s difficult to conclude anything. For example, human networks contain words that are have many connections to many other words (words such as food, money or water). Such vertices are also called hubs, as they appear in many different contexts and act as intermediaries linking different groups of words. As it turns out, the synthetic networks contained fewer such hubs and those were quite different words (e.g., even, way, nothing, know). However, some of the synthetic networks with such hub-words have shown similar clustering pattern as the human networks – the neighbors of such words are less likely to be neighbors themselves. One way to think about this is to imagine that neighbors of a certain word “live” far away from each other (in the image above, the word food has connection to hygiene and bread, but bread and hygiene are not connected). More in-depth details about how to quantify these clustering tendencies can be found in my technical report.

Analysing word networks is fun, but why does it matter? For one, it matters in applications where the goal is to simulate aspects of human linguistic behavior. Usually, cognitive modellers are faced with a choice of what semantic model to use to approximate some aspects of human knowledge of cognitive ability. That choice can be guided by evaluating whether relevant aspects of the semantic model used resemble that of human semantic networks. The second reason is that such analyses provide basic insights into differences between the way humans think about words and the way machines “think” about words, which could have a number of important implications for designing more human-like AI systems.

References

[0] Collins and Quillian, Retrieval Time From Semantic Memory (Journal of verbal learning and verbal behavior, 1969)

[1] Collins and Loftus, A spreading-activation theory of semantic processing (Psychological Review, 1975)

[2] Huth et al., Natural speech reveals the semantic maps that tile human cerebral cortex (Nature, 2016)